Locations

For further factual background and our analysis of previous interim and related appeal judgments, check out our previous SnIPpets posts:

- Lidl victory against Tesco in relation to bad faith counterclaim and survey evidence; and

- Fresh hope for Tesco in trade mark infringement clash with Lidl.

Summary of findings

In a comprehensive 102-page judgment, Smith J found:

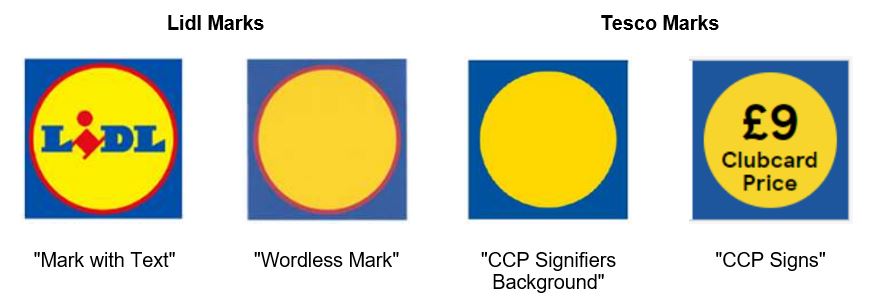

- Tesco's use of the CCP Signs constituted trade mark infringement of both the Mark with Text and the Wordless Mark;

- In relation to Tesco's counterclaim seeking to invalidate Lidl's Wordless Mark on the grounds of non-use and bad faith:

- Lidl had used the Wordless Mark (and therefore it could not be revoked for non-use);

- However, the Wordless Mark was invalid on the basis that it was registered in bad faith;

- Tesco's use of the CCP Signs constituted passing off; and

- Tesco's CCP Signs infringed copyright in Lidl's Mark with Text.

These findings are discussed in more detail below. Smith J also invited the parties to liaise over the terms of the order giving effect to the judgment, so it is possible there may be further hearings and judgments.

Trade mark infringement

Lidl relied solely on s 10(3) Trade Marks Act 1994 ("TMA") to support its claim that Tesco's use of both the CCP Signifiers Background and CCP Signs infringed both the Mark with Text and the Wordless Mark. At trial, Lidl conceded that Tesco did not use the CCP Signifiers Background by itself (i.e. the background icon without any additional text). In that context, Smith J found that the "correct comparison is quite obviously between the Lidl Marks and the CCP Signs".

Section 10(3) is designed to protect only registered trade marks that have reputation against specific forms of damage. In order to succeed under s 10(3), Lidl was required to prove a number of distinct elements, namely:

|

The elements bolded above were key areas of dispute between the parties. After considering the relevant case law and evidence, Smith J found, in relation to the Mark with Text:

- In terms of similarity, the CCP Mark was similar to the Mark with Text ( i.e. the below marks are similar):

and

and

Despite counsel for Tesco's eloquent observation that use of other text, including the word "Clubcard" in the CCP Mark, was sufficient to "block out the sun", Smith J ultimately found that the overall impression was one of similarity:

"The visual similarity is here the significant feature and, whilst I accept that the text represents an important point of difference, nonetheless I do not consider that it has the effect of extinguishing the strong impression of similarity conveyed by their backgrounds in the form of the yellow circle, sitting in the middle of the blue square. This was an impression that I formed myself upon seeing the Mark with Text and the CCP Signs."

In coming to this conclusion, the Judge noted she was "fortified" by the evidence demonstrating that during the creation of the CCP Mark, several members of the Tesco team had themselves noted there was similarity to Lidl's mark

- In terms of unfair advantage, an average consumer would draw a link between CCP Signs and the Mark with Text as there was "clear evidence of both origin and price match confusion/association together with evidence that Tesco appreciated the potential for confusion." In particular, the evidence showed that the CCP Signs were used near signage advertising Tesco's price-matching campaign with Aldi (another German budget supermarket). Survey evidence also showed that a number of shoppers viewing the CCP Mark assumed Tesco was price-matching with Lidl (when it was not). Confusion of course is not necessary to establish infringement under s 10(3) TMA but its existence here helped establish the necessary link. Smith J noted that she did not consider that Tesco deliberately intended to "coat-tail" on Lidl's reputation, but she found that intention was not necessary to establish unfair advantage.

- In terms of detriment, Smith J found that:

- Lidl established detriment to the distinctive character of its Lidl Marks, evidenced by the fact that it had found it necessary to take evasive action in the form of corrective advertising. In particular, Lidl gave evidence that it had decided to pursue an "Unmatched Value" price comparison campaign targeted at Tesco's "Clubcard Prices" when it realised there was an increased market perception that Tesco offered greater value on price.

- Tesco had obtained an unfair advantage, because the use of the CCP Signs had resulted in “a subtle but insidious transfer of image” from Lidl's Marks to the CCP Signs in the mind of consumers.

- Lastly, in relation to the absence of due cause, Smith J rejected Tesco's contention that it had due cause to use the CCP Sign, which consisted of the colour blue (as its own livery colour), eye catching yellow and simple shapes. These arguments did not establish due cause in respect of the specific combination of features used in the CCP Signs as a whole. In coming to this conclusion the Judge referred to the evidence showing the Tesco team were told that using the CCP Sign was "non-negotiable", which sat at odds with Tesco's assertion that the CCP Sign had been a "speculative selection". Smith J also drew an adverse inference from Tesco's failure to explain why the choice of the CCP Mark was "non-negotiable" and its decision not to call its external creative agency to give evidence.

In light of the findings in relation to the Mark with Text, it was not strictly necessary for Smith J to rule on infringement related to the Wordless Mark. Nevertheless, she concluded that the position on infringement was the same.

Rather unusually, Lidl did not rely on s 10(2) TMA which protects registered trade marks from third party use of an identical/similar sign in relation to identical/similar goods or services, where there is a likelihood of confusion. Instead, Lidl solely relied on its reputation in the Lidl Marks and focussed its evidence on proving that the CCP Sign took advantage of Lidl's reputation for great value among British consumers.

Counterclaim – non-use and bad faith findings

Given Smith J's findings in relation to infringement of Lidl's Mark with Text, the Counterclaim by Tesco to revoke or invalidate Lidl's Wordless Mark did not advance Tesco's position. Nevertheless, Smith J briefly dealt with the arguments advanced by the parties.

In relation to the allegation of non-use, Smith J found in favour of Lidl. Specifically the Court found that Lidl's historical use of the Mark with Text constituted use of the Wordless Mark (despite the fact that Lidl never used the Wordless Mark on a standalone basis):

- Relying on the CJEU judgment in Specsavers International Healthcare Ltd v Asda Stores [2013] ETMR 46, Smith J found that the addition of the text "Lidl" did not alter the distinctive character of the Wordless Mark;

- This conclusion was supported by Lidl's YouGov survey evidence, which showed that consumers associated the Wordless Mark with Lidl (i.e. even where the word "Lidl" did not appear on the logo).

In relation to the allegation of bad faith, Smith J found in favour of Tesco. Specifically, the Court found that:

- It was bound to accept the Court of Appeal's finding (see here) that the facts as pleaded by Tesco were sufficient to shift the evidential burden of proving good faith to Lidl. The relevant pleaded facts were:

- There had never been a genuine intention to use the Wordless Mark, which was instead designed as a "legal weapon". Lidl already had a registration for the Mark with Text for the same goods and services at the time the Wordless Mark was filed;

- Lidl had engaged in "evergreening" of the Wordless Mark, that is the periodic re-registration of the Wordless Mark for the same or similar services to avoid sanctions related to five years of non-use.

- The evidence relied upon by Lidl at trial was not sufficient to prove good faith. Unsurprisingly (given how much time had passed since the first Wordless Mark was filed), Lidl did not have any contemporaneous evidence of its subjective intention to use the Wordless Mark at the time of filing in 1995. Instead, the evidence was limited to Lidl's current trade mark filing strategy, which Smith J found could not speak to the position in 1995.

- The tenor of the analysis suggests Smith J felt her hands were tied on bad faith:

The Wordless Marks filed in 1995, 2002, 2005 and 2007 were therefore invalid for bad faith. However, the Wordless Mark application filed in 2021 (after Lidl had written to Tesco asking it to cease and desist from using the CCP Sign) was not invalid for bad faith. The Judge found that the 2021 application did not follow an "evergreening" pattern, as it was filed 11 years after the last application. However, there was very little discussion on this mark (which was applied for in every class except class 45). It is interesting that Tesco did not seek to invalidate that mark for lack of intention to use.

Passing off

Lidl asserted a claim in passing off on the ground that, by use of the CCP Signs, Tesco misrepresented that products sold by Tesco shared the qualities of those of Lidl, including that they were sold at the same or equivalent price, or had otherwise been price matched with Lidl products. Accordingly, Lidl's case was founded in a misrepresentation as to equivalence, rather than a misrepresentation as to origin.

After considering the settled authorities related to the elements of passing off and the evidence, Smith J found:

- In relation to goodwill, that Lidl had established goodwill in the UK as a "discounter that offers goods at low prices".

- In relation to misrepresentation, that the body of evidence, and in particular Tesco's deployment of the Aldi price-matching campaign, suggested that a substantial proportion of consumers would be deceived by the CCP Signs and believe that Tesco's "Clubcard Prices" were the same as or lower than the prices offered by Lidl.

- In relation to damage, that Lidl suffered damage for the same reasons discussed in the analysis of "unfair advantage" in the context of trade mark infringement. In doing so, Smith J rejected Tesco's contention that even if consumers were deceived, there could be no damage because the evidence showed that Tesco's Clubcard prices were in fact equivalent to Lidl's prices. In Smith J's opinion, even if prices were the same (or cheaper), consumers may mistakenly believe they do not need to check to compare prices (as the CCP Signs suggested that Tesco had already completed this comparison exercise, when they had not).

In a small win for Tesco, Smith J rejected Lidl's claim that Tesco deliberately intended to mislead consumers, notwithstanding the fact that some of the evidence showed that certain Tesco employees understood the CCP Signs to be reminiscent of Lidl's Marks. However, later in the judgment, Smith J concluded that "despite internal disquiet, Tesco ultimately convinced itself that the CCP Signs would involve no misattribution to Lidl."

Copyright infringement

At trial, Lidl's claim for copyright infringement under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 was narrowed to the following: (1) Lidl owned the copyright in the artistic works comprising the Mark with Text; and (2) Tesco had copied a substantial part of the Mark with Text in the CCP Signs.

In relation to copyright subsistence, Smith J found that Lidl owned the Mark with Text as an artistic work. Furthermore, the logo satisfied the test for originality, despite Tesco's claims that creation of the logo involved negligible artistic skill and labour and used "kindergarten shapes". Indeed, Smith J found that Tesco's own evidence about the design process involved with the creation of the CCP Signs undermined this argument:

"Someone in the employ of Lidl took the Lidl text and the yellow circle with the red border and superimposed them on a blue background to create the Mark with Text. On balance, I consider that this is likely to have involved time, labour and creative freedom (even if the artistic quality involved is not “high”). Tesco’s own evidence as to the various combinations of apparently basic shapes and colours considered by its own designers in arriving at a decision as to the CCP Signs tends, in my judgment, to bear this out."

In relation to copying a substantial part, Smith J found that:

- The similarities between the Mark with Text and the CCP Signs were "sufficiently close that they are more likely to be the result of copying rather than mere coincidence".

- When considering the question of substantial part quantitatively rather than qualitatively, the blue background with the yellow circle formed a substantial part of the Mark with Text.

When considering the question of copying, Smith J noted that the evidence from Tesco in relation to the design of the CCP Signs presented an "inaccurate and incomplete picture". Furthermore, Smith J drew adverse inferences from Tesco's failure to adduce any evidence from their external creative agency involved in the design of the CCP Signs, concluding that "I can only infer that such evidence would have been adverse to Tesco’s case on the development of the design of the CCP signifier."

Takeaways

Given the size of the judgment and the array of aisles explored, it is difficult to narrow the key takeaways into one neat basket. Some of the high points are outlined below:

- First, Lidl's success under s 10(3) TMA is owed in large part to the comprehensive evidence used to prove its claim, including top-shelf survey evidence (supported by expert evidence) and lay evidence from consumers. The judgment includes an extremely detailed analysis of the parties' evidence to support the elements under s 10(3) and explains how Lidl satisfied these requirements through its evidence (and was relatively critical of Tesco's evidence by comparison). This case should also fortify IP lawyers who may be hesitant to rely on survey evidence that survey evidence done properly can make a case (like it did for Lidl).

- Secondly, while non-use and bad faith were ultimately toothless tigers in this case, the discussion on these points provides interesting guidance on the type of evidence required to defend non-use and bad faith allegations. There are a number of recent and ongoing cases concerning the law regarding bad faith in the context of "evergreening" (for example the Sky v Skykick dispute which is heading to the Supreme Court in June). This judgment shows that, provided a bad faith case is properly pleaded, trade mark owners who engage in "evergreening" may find it difficult to overcome allegations of bad faith in the absence of contemporaneous evidence showing good faith at the time of filing.

- Lastly, Tesco has issued public statements indicating it will appeal the judgment. Given the length of the judgment and the array of findings, it will be interesting to see where the appeal points will lie, given that most of the findings are tied to the Judge's perception of the credibility of witnesses and the documentary evidence before the Court. However, reasonable minds may differ as to whether the authorities support the conclusion that the Mark with Text and CCP Signs are "similar" for the purposes of trade mark infringement under s 10(3), or whether Tesco copied a "substantial part" of the Mark with Text for the purposes of copyright infringement. Furthermore, it will be interesting to see whether Lidl cross-appeals the finding on bad faith and seeks to reinstate its registrations for the Wordless Mark.

Watch this space for further updates.