Locations

Scenario

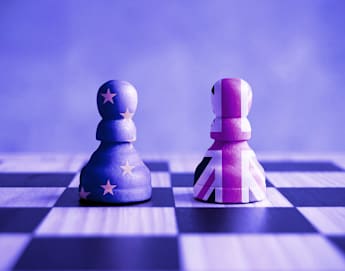

Picture this: it's November 2020. Press releases from the UK and the EU make it clear that although progress is being made, negotiations for an EU adequacy decision in favour of the UK are ongoing and have some months still to run.

Your company has put in place measures to ensure that personal data can continue to flow from your suppliers in the EU to your headquarters in the UK, using the European Commission's new standard contractual clauses. But your Data Protection Officer gets in touch and says that there has been advice from the UK government and the Information Commissioner's Office explaining that in light of the fact that no adequacy agreement is in place, companies need to map the personal data they are processing in the UK. Your company therefore needs to tag the "UK data" to distinguish it from personal data of data subjects outside the UK which is processed in accordance with EU law in the UK headquarters prior to the end of December 2020 – ie the "non-UK data".

You phone your CEO to explain the position and ask for the release of some funding to do this. Your CEO says "but surely there's no difference between how you treat "UK data" and "non-UK data"? The UK government has decided to keep the GDPR as national law so all data in the UK gets treated in the same way."

You get in touch with your in-house counsel who explains "Well that's true. But the reality is more complex. "Non-UK data" and "UK data" will be subject to the same standards to begin with, because the UK is keeping the GDPR and turning it into UK national law, but the UK courts are going to start moving away from the old interpretations of the GDPR under draft legislation which is about to come into force. Also, UK courts aren't required to follow judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union which are handed down after 31st December 2020 when deciding how to interpret the UK version of the GDPR.

By contrast, under Article 71 of the Withdrawal Agreement, "non-UK data" has to be processed in accordance with the GDPR as it stood on 31st December 2020 and interpreted in accordance with both existing and future judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

All this means that it’s inevitable that the UK version of the GDPR (which will apply to "UK data") and the version of the GDPR which applies to "non-UK" data will start to diverge. The only way to solve the "non-UK data" and "UK data" dilemma is to have an adequacy decision, but that won't be coming for ages, from what I've heard. So we do need to get cracking with sorting the "UK data" from the "non-UK data" asap."

In-house counsel goes on: "That's not the end of our problems. I've also just heard that the European Commission is updating the GDPR. If that happens, then this will be a further complication. When we open the new Amsterdam branch of our UK headquarters, the UK headquarters will most likely be subject to three different sets of data protection rules: First, the updated GDPR (because the UK headquarters will be established in the EU through the Amsterdam branch), second, the GDPR as it stood on 31st December 2020 for "non-UK data", and third the UK GDPR for "UK data". Mapping how that works is going to be like playing three-dimensional chess."

"What do you mean", you ask?

"Well", says in-house Counsel. "Imagine it's summer 2021. The UK as yet has no adequacy decision from the EU. The Court of Justice of the European Union hands down a judgment about when subject access requests can be deemed to be excessive under the GDPR. It sets the bar incredibly high because of the importance of data subject rights. The UK courts hand down a judgment the following week on the same issue but take a much more generous view of when a request can be deemed to be excessive on the basis that data subject rights are not absolute and the resource being taken up answering such requests is often disproportionate. At the same time, the European Commission announces proposed changes to the GDPR, amongst which is an initiative to abolish the "excessive" test altogether.

So we will have to redraft our data subject rights policy to apply the Court of Justice's ruling on "excessive" requests as they apply to non-UK data and the UK court's decision for UK data. But when the GDPR is updated then because of the Amsterdam branch that update will also apply to the UK headquarters. How we navigate these three different approaches to whether a request is excessive will not be straightforward".

How far-fetched is this scenario? Unfortunately, it isn't far-fetched at all. This article seeks to examine how this scenario could become a reality.

Overview

The UK will leave the EU on 31st January 2020. When it leaves, the Withdrawal Agreement between the UK and the EU will kick in. The Withdrawal Agreement ensures that the UK will (subject to some exceptions) be treated as an EU Member State while the UK and the EU negotiate a trade deal. This ensures that there will be no sudden changes in the UK's legal arrangements on 31st January. The timeframe during which the UK is treated as if it is an EU Member State is called the transition or implementation period.

The UK Government intends that the transition or implementation period should last only 11 months, until 31st December 2020. That is a very short timeframe indeed for a new trading arrangement to be negotiated between the UK and the EU. Although the Withdrawal Agreement allows the transition period to be extended once to the end of 2021 or 2022 the UK Government has proposed legislation which would prevent it from applying for an extension (see clause 33 of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill, which implements the Withdrawal Agreement in UK domestic law).

All this means that there is a significant likelihood that at the end of the transition period there will be no deal in place between the UK and the EU in relation to significant areas of the UK economy.

From a data protection perspective, the GDPR will apply in the normal way during the transition period (subject to some exceptions, for example the UK's Information Commissioner will not automatically be entitled to attend the meetings of European regulators – the European Data Protection Board – during the transition period). However, the transition period may well come to an end on 31st December 2020 without the EU having made an adequacy decision in favour of the UK.

The Withdrawal Agreement foresees this gap between the end of the transition period and an EU adequacy decision in favour of the UK. This is where the complexities of Article 71 of the Withdrawal Agreement become clear.

What does Article 71 of the draft Withdrawal Agreement say?

Article 71 does three things:

• Article 71(1) ensures that personal data of data subjects outside the UK, which is processed in the UK, must be processed in accordance with EU law as it stands at the end of the transition period where it was processed:

- under EU law before the end of the transition period (including during the UK’s EU membership), or

- after the transition period under the Withdrawal Agreement, for example pursuant to the provisions on citizens' rights

• Article 71(3) provides that if the UK loses its adequacy decision it must apply protections to personal data within the scope of Article 71(1) which are ‘essentially equivalent’ to EU law standards.

What are some of the problems raised by Article 71?

The reality is that it is going to be difficult to get adequacy decisions (under both the GDPR and the Data Protection Law Enforcement Directive, Directive (EU) 2016/680 (DPLED)) for the UK if the transition period lasts only until 31 December 2020. The quickest EU adequacy decision so far (relating to Argentina) took 18 months.

The UK will adopt the GDPR as national law and turn it into the ‘UK GDPR’ at the end of the transition period. However, this doesn’t mean that a favourable decision on EU adequacy for the UK will be easy or automatic.

National security

One area where adequacy negotiations may prove challenging is in the context of the UK’s legislation relating to national security. During the UK’s EU membership, the European Commission was not entitled to consider the UK’s legislation in the area of national security, which is an area outside EU competence (see Article 4(2) of the Treaty on European Union). Once the UK leaves the EU, legislation in the field of national security is one of the areas the Commission is required to examine in order to decide whether an EU adequacy decision should be conferred or not - see Article 45(2)(a) of the GDPR. Similar provisions apply in Article 36(2)(a) of the DPLED. Commentators expect that the UK’s Investigatory Powers Act 2016, which deals with interception of citizens’ data, may create some difficulties.

The Commission’s programme of work

A further potential complication is that the Commission already has a busy programme of work in the context of data protection. The new version of standard contractual clauses may need amending to take account of the judgment in Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited, Maximillian Schrems, Case C-311/18. The review of the adequacy decisions made under the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC (the legislation which the GDPR replaced), is due to be completed by May 2020. Adequacy negotiations are also ongoing with South Korea.

If the transition period ends on 31 December 2020 with no UK adequacy decision in place, then Article 71(1) would have to be implemented in UK law.

What are the implications of Article 71(1) for UK organisations?

Article 71(1) represents something of a safety net for the personal data of data subjects outside the UK which is processed in the UK.

As set out above, this safety net operates in relation to personal data from outside the UK which was processed in the UK:

• under EU law before the end of the transition period (including during EU membership); or

• after the transition period under the Withdrawal Agreement (for example, pursuant to the citizens’ rights provisions).

Non-UK data must be processed in accordance with ‘Union law on the protection of personal data’ (meaning the GDPR, DPLED, the ePrivacy Directive 2002/58/EC, and any other provisions of EU law governing the protection of personal data).

This means that non-UK data held by UK businesses will have to continue to be processed in accordance with the GDPR and such other EU laws as they stood on the last day of the transition period (see Article 6(1) of the Withdrawal Agreement which defines Union law as EU law ‘including as amended of replaced, as applicable on the last day of the transition period’).

In some ways this will make no difference for UK organisations because the default position is that the UK will save the GDPR into domestic law at the end of the transition period. So, the same cut-off point applies and the same standards will be ‘saved’ under the Withdrawal Agreement as in UK domestic law. This means that processing data under the GDPR in accordance with Article 71(1) or under the UK GDPR will make no operational difference. The data will simply be treated in the same way.

The reality, however, may be more complex. The GDPR as it stood on 31 December 2020 will inevitably start to move away from the UK version of the GDPR. That is because even if the UK government does not make further or extensive amendments to the UK GDPR, the UK courts will interpret and develop the UK GDPR. The current version of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill would allow the UK courts to diverge more quickly from the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) than under the policy pursued by Theresa May's government. Previously only the Supreme Court and the High Court of Justiciary in Scotland would have been entitled to depart from the retained case law of the CJEU (see section 6(4) and (5) of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018). The policy behind that was to ensure that the interpretation of EU law as retained in the UK after Brexit would stay the same – in other words continuity was deemed to be important. Under the Withdrawal Agreement Bill there are powers to make secondary legislation which would allow more courts to diverge from the retained case law of the CJEU (or retained domestic case law which relates to the retained case law of the CJEU) on the basis of a test which is yet to be determined (see clause 26(1)(d) of the current draft of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill). If such legislation is brought into force then divergence may happen relatively quickly. Further, the UK courts will not be required to follow the judgments of the CJEU handed down after the end of the transition period (see s 6(1) of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018).

The position under the UK GDPR (particularly in relation to the case law of the CJEU) is different from the position in relation to the GDPR under Article 71(1). When interpreting the GDPR in accordance with Article 71(1), the UK courts will be required to have due regard to the relevant case law of the CJEU handed down after the end of the transition period (see Article 4(5) of the Withdrawal Agreement). This divergence in approach relating to post-transition period case law of the CJEU is likely to take the GDPR under Article 71(1) and the UK GDPR in different directions.

In addition, over time, the UK may choose to legislate for divergent positions.

A ‘headache’ for UK business?

Further, UK organisations may not know which standards apply because they may not know whether the data they hold was originally from outside the UK or within it. This is especially true of commercial organisations. Without information about where the relevant data comes from it will be impossible for UK organisations to be clear that they are complying with both regimes. The answer might simply be to delete or anonymise legacy data, but databases can be extremely valuable and simply deleting one of a company’s most significant assets is hardly an appealing prospect.

Where there is a contradiction between UK domestic law and the Withdrawal Agreement, the Withdrawal Agreement takes precedence (see Article 4 of the Withdrawal Agreement and subsections 2 and 3 of the new section 7A of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 as inserted by clause 5 of the Withdrawal Agreement Bill). So when it comes to non-UK data the provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement (including Article 71 and the relevant CJEU case law) take precedence over any conflicting UK domestic legislation or case law. However, this does not fully solve the potential complexities.

A further headache for larger UK organisations is that their operations in the EU may mean that they are established in the EU and therefore subject any updated version of the GDPR. Alternatively, UK organisations may be caught by the GDPR’s provisions on extra-territorial scope (for example when selling goods or services into the EU). This may mean that they are subject to the GDPR, the Article 71(1) version of the GDPR and the UK GDPR (which may start to evolve in an altogether different direction). This could end up causing significant barriers to trade because companies will simply deem compliance with all these regimes too complex and costly.

Conclusion

This points to the necessity of gaining EU adequacy decisions in favour of the UK in order to ensure that this highly undesirable outcome does not transpire. In the absence of EU adequacy decisions Article 71(1) causes considerable headaches for UK companies. It also underscores that diverging standards in the field of data protection present a significant challenge.

This post is based on an article which was originally published on LexisLibrary and LexisPSL.