Locations

Factual Background

Emson is the exclusive licensee of a UK and European Patent for an expandable garden hose, comprising an elastic inner-tube and a non-elastic outer-tube, which is compact when empty but expands and lengthens under pressure when filled with water ("the Xhose"). The hose pipe was developed by Mr Berardi in his home in Florida, with several prototypes being developed in his garden. The patented product was commercially successful, resulting in Hozelock developing and selling a rival product in the UK ("the SuperHose"). Emson issued infringement proceedings in the UK and Hozelock counterclaimed to invalidate the patents.

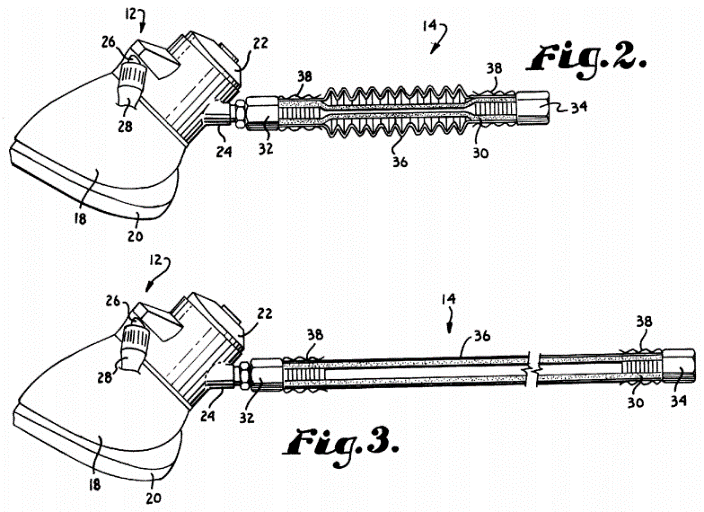

At first instance, in June 2019, Mr Justice Nugee held that the patents were not disclosed by Mr Berardi when working on the prototypes in his garden in Florida. Nevertheless, the patents were invalid for being obvious in relation to a prior art patent known as McDonald. McDonald related to a self-elongating oxygen hose for stowable aviation crew oxygen masks, which disclosed to the skilled reader a self-elongating hose comprising an elastomeric inner-tube and an outer-sheath which expanded axially when pressurised – illustrated below.

Both McDonald and the Xhose rely on pressure to elongate: air pressure in the case of McDonald, water pressure in the case of the Xhose and the Berardi patent.

The McDonald patent is in a very different field - aircraft breathing apparatus - and very unlikely ever to have been read by a person interested in garden hose design. It is trite law, however, that the skilled person in the field of garden hoses nevertheless would read McDonald, and not simply dismiss it just because it is in a different field. Further it "is undoubtedly the law that an invention may habe been published in, or rendered obvious by, a document which no person skilled in the art would ever be likely to have seen." (Floyd LJ).

Emson appealed the judgment to the Court of Appeal on the basis that Mr Justice Nugee had erred by: (1) conducting an ex post facto, hindsight-based analysis of obviousness; and (2) failing to take into account the commercial success of the Xhose in that analysis.

Court of Appeal judgment

Lord Justice Arnold, with whom Lord Justice Henderson agreed, noted that it was common ground between the parties that the patents are addressed to a person interested in the design and manufacture of garden hoses. It was clear from the judgment that Mr Justice Nugee had been conscious of the need to avoid hindsight when assessing obviousness. The Court of Appeal needed to consider whether nevertheless the judge fell into error in this respect.

When assessing obviousness, under the UK's Pozzoli test (which set out a four-step approach), Lord Justice Arnold noted that McDonald relates to aerospace, an entirely unrelated field to garden hoses. However, the invention in McDonald was an elongating hose and no technical reason had been identified for the skilled person thinking that the hose in McDonald was unsuitable for garden use.

The problem addressed by McDonald was saving space, which is one of the problems addressed by the Xhose patents. Once aware of McDonald, it would not be a giant leap for the skilled person to recognise its use for garden hoses. The skilled person would be interested in solving the problems with garden hoses of space, weight and kinking – the question was whether, upon reading McDonald, it would be obvious to the skilled person to adopt the same principles for a garden hose. The fact that the invention in McDonald was never commercialised was relevant, however there was no evidence that this was because the invention did not work or had been disregarded.

Regarding the commercial success of the Xhose, there was no evidence that McDonald was known to those in the hose industry. Therefore, the commercial success of the Xhose did not help to evidence the inventiveness of the patents over McDonald. In conclusion, the appeal was rejected by Arnold LJ and Henderson LJ.

Lord Justice Floyd dissented. He agreed that the commercial success of the Xhose, which was of "breath-taking ingenuity", did not assist Emson with the assessment of obviousness because the prior art in question (McDonald) was not part of the same field so was unlikely to have been seen by the person skilled in the art. However, he thought it was not right to say a mere paper proposal could be successfully implemented if there was no evidence that over a substantial period of time it had been implemented. Therefore, the judge in Floyd LJ's view made a number of fundamental errors when assessing obviousness.

First, he treated McDonald as a real practical machine as opposed to a mere paper proposal. The conclusion that the skilled persons interested in garden hoses would view McDonald as useful ought to have been treated with scepticism, as the skilled person would not know that it actually would work, i.e. that it would be useful, even in the field of aircraft breathing apparatus. Similarly, the evidence from the experts in the proceedings was that they did not fully understand the detail of how McDonald worked, suggesting the judge's assessment of its usefulness to garden hoses had been with hindsight.

Lord Justice Floyd's view was that the skilled person might be more interested in a document if it solved a problem they were facing, but space-saving had already been solved in the field of garden hoses (e.g. through the use of a reel). The Xhose was a leap forward because it solved three problems: space-saving, lightness and no kinking. McDonald did not present the skilled person solutions to all of these problems. The fact that the design of garden hoses had not changed for many decades was also a material factor that ought to have been taken into account. The idea that that the notional, unimaginative skilled person with an interest in this industry would seize on an untested proposal from a "very particular and very distant field" and taken it further had the air of unreality - i.e. it was not obvious that it would be taken further. Accordingly, in Floyd LJ's judgment, McDonald did not render the Berardi patent invalid. However, because Floyd LJ was in a minority, his judgment was not effective to overturn Nugee J's earlier judgment.

Comment

The Xhose was brilliantly simple and radically different to the design of garden hoses, which had gone unchanged for many decades. Nevertheless, the invention was deemed obvious in light of a niche patent document in the field of aerospace of which Mr Berardi was unaware. The inventive concept underlying the Xhose was unambiguously disclosed in that niche patent document. The key question was what the skilled person would do in relation to that earlier document. Lord Justice Arnold's view was that it would have been obvious to utilise the prior art in the field of garden hoses, whereas Lord Justice Floyd disagreed.

This is not the first time that the validity of the Berardi patent over McDonald has been before the English court. In an earlier case (Blue Gentian LLC v Tristar Products (UK) Ltd), Birss J concluded that it was not invalid over McDonald. So the track record now is that two judges (Birss J and Floyd LJ) consider that the Berardi patent is not obvious in light of McDonald, and three Judges (Nugee J, Arnold LJ and Henderson LJ) consider that it is obvious. This illustrates how finely balanced this question is when considering prior art that is unrelated and a paper proposal. The score is yet more evenly balanced when one also includes Opposition proceedings at the EPO - there the conclusion was that it was not obvious.

In the UK, the "state of the art" comprises anything which is disclosed anywhere in the world and free in law and equity, regardless of whether it falls within a separate technical field. In this case, once the prior art was placed in the skilled person's hands, it was difficult to argue that the skilled person would not apply it to the field of garden hoses given the fact that it unambiguously disclosed the invention. Lord Justice Floyd's point was that the skilled person is uninventive and, where the prior art has not been embodied in a commercial product for a substantial period of time, it is a leap to say the skilled person would, nevertheless, use the prior art to solve problems which the prior art did claim to solve.